An intricate dance of turbulence and gravity

July 27, 2023

Mesmerizing, isn’t it? But what exactly is going on here?

What you’re looking at is a giant molecular cloud of \(10,000~\mathrm{M}_\odot\) (solar masses), embedded in the interstellar medium (ISM), evolving under turbulence and self-gravity. The size of the cloud is roughly \(17~\mathrm{parsec}\) (or 55 light years). These molecular clouds are cold, dense regions of the ISM, primarily composed of molecular hydrogen (H2). Cold, because the temperature is around \(10 \mathrm{ - } 20 ~\mathrm{K}\), and dense, because the number density of particles is \(>100~\mathrm{cm}^{-3}\). Note that the density of the Earth’s atmosphere is \(\sim10^{19}~\mathrm{cm}^{-3}\), far denser than these clouds! In space, everything is relative, so compared to the ISM where the density is \(\sim10^{-4}~\mathrm{cm}^{-3}\), these clouds are indeed dense. Galaxies often contain thousands of these types of clouds. They form birth-places of stars, and are crucial to our understanding of how galaxies evolve to give rise to the stars we see today.

How are these simulations performed?

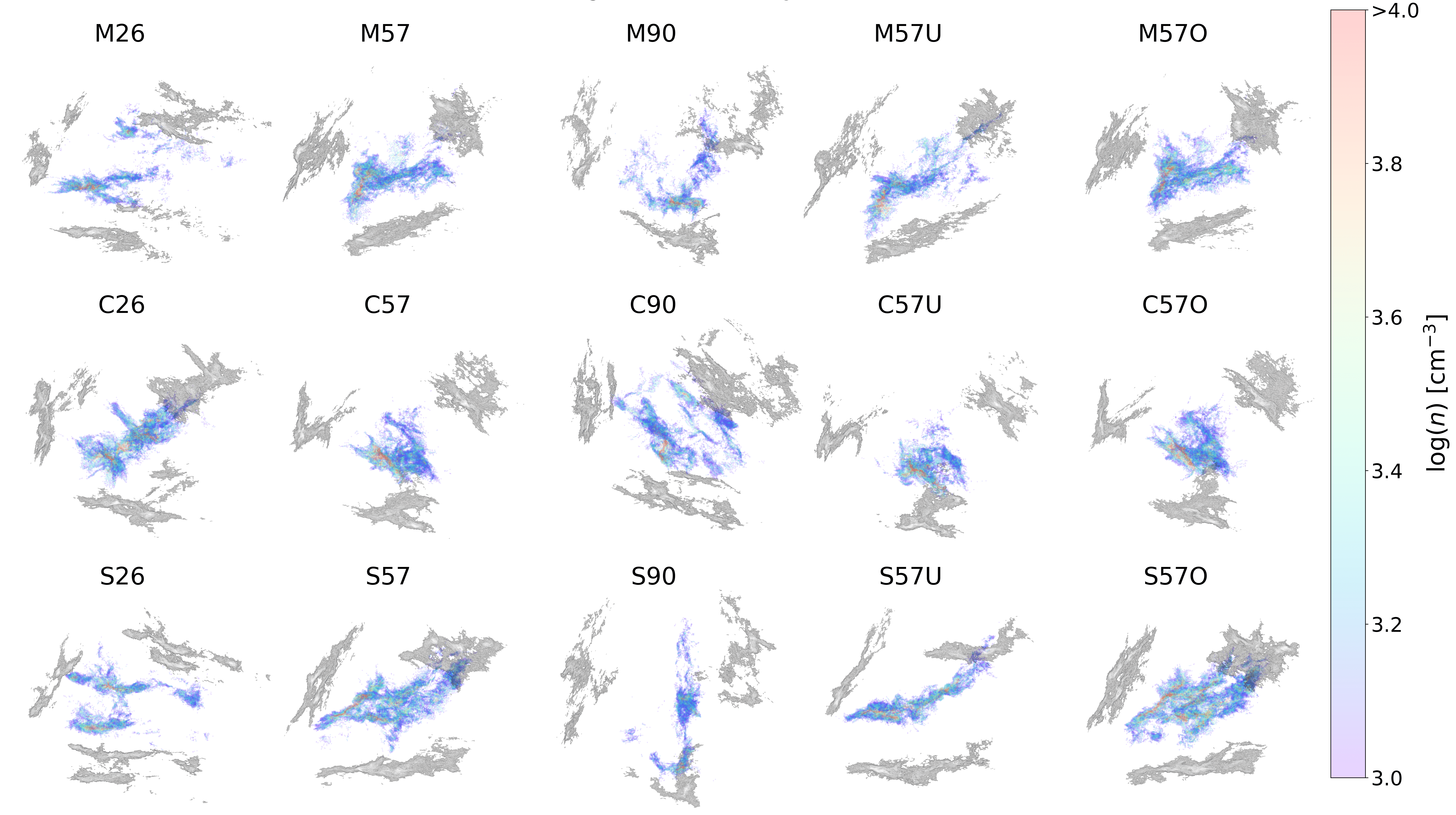

The simulations shown here were perfomed using the adaptive mesh refinement code \(\texttt{AREPO}\). The cloud is initially spherical, and is set into motion by a turbulent velocity field, different for each panel in the video above. Since the cloud is gravitationally unstable, it collapses to form stars. In 3D, they clouds looks like this:

where the colour represents the density of the gas, red being the densest. What gives rise to this turbulence? In reality, it could be a variety of sources: large scale events like shear forces in spiral arms of galaxies, magnetic instabilities; local events like supernovae, stellar winds; or even the cloud’s own gravity. In the simulations, we inject turbulence via the initial velocity field and let in decay as the cloud is evolved in time. The simulations are run for a few million years (Myrs), enough time for the cloud to collapse and form stars. The simulations are run on supercomputers, and take days to complete a single run.

Why are these clouds important?

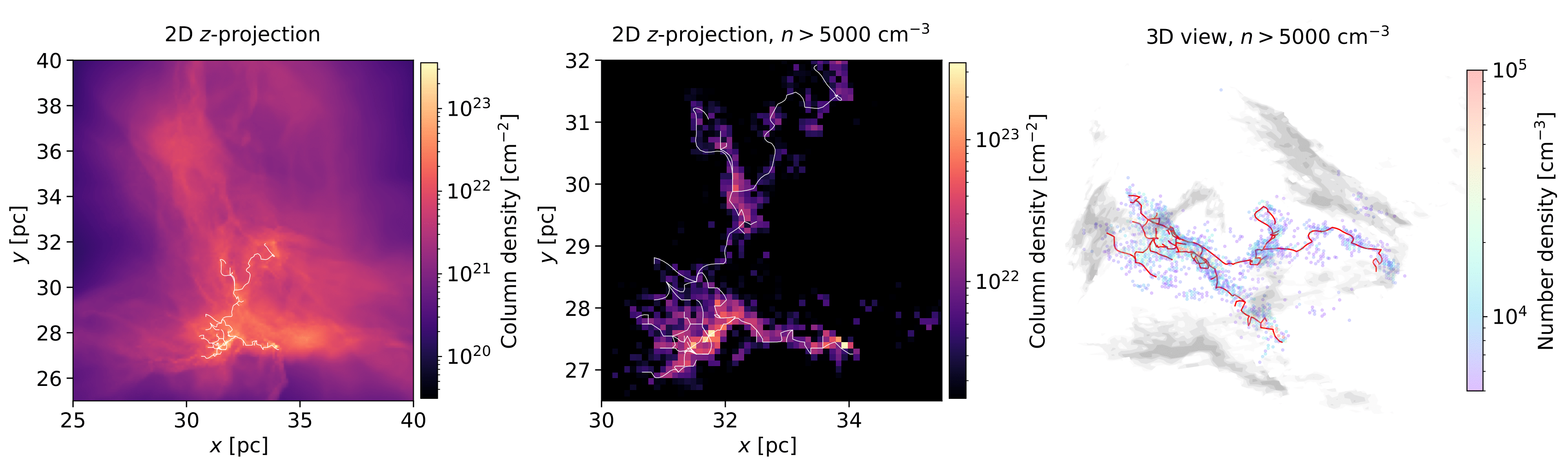

An interesting aspect of these clouds is that during collapse, they form a network of thin, dense lines (filaments) which are hot-spots for star formation. Our current understanding is that dense clumps form preferentially along these filaments, like beads on a string, and eventually collapse to form stars and stellar clusters. Below is a snapshot of a single cloud mid-collapse, with filaments traced using \(\texttt{DisPerSE}\), a filament-finding algorithm.

Massive stars and hubs

Any filamentary network will have regions where multiple filaments converge, like highways at a junction. These regions would be enormously dense, called hubs, where some of the most massive stars \(>8~\mathrm{M}_\odot\) can be birthed. They are very important for the evolution of galaxies, as massive stars emit a lot of radiation, stellar winds, and eventually go supernovae, recycling all of their gas and matter back into the ISM and hence regulating it. The relation between hubs and massive stars is exactly what we intended to explore as part of my Master’s project at the University of Manchester. For more details, check out the published paper below, 2 years in the making and my very first first-authored work!